Every writer needs an editor. Another pair of experienced eyes can strengthen any written work. But there’s a right way and a wrong way to edit.

First, let me clarify that there are several kinds of editing, generally falling into these three categories:

• Developmental, substantive, or structural editing helps give overall shape to the piece: what to include or exclude, how to control the pacing, and how to make sure that the piece flows logically from beginning to end. This kind of editing should be done fairly early in the process, and it’s what a critique group ought to do. It’s “big picture.”

• Copyediting or line editing is what most people who aren’t trained as editors (yes, you can go to school for that) think of when they think of “editor.” Copyediting should fix grammar, usage, tangled syntax, and mistakes, and in general should polish the prose. This is what I’m going to be talking about because this is where wannabe editors get confused and abusive. Copyediting works at the paragraph and sentence level.

• Proofreading or mechanical editing checks for typos and makes sure that a style sheet is applied (whether you abbreviate months, spell out numbers, and so on). This is sometimes confused with copyediting by wannabe editors who are tasked to proofread but who get over-ambitious. Proofreading should look at the individual words and punctuation marks.

How do you copyedit correctly? Here is the rule: Only suggest changes to correct an objective error or problem. “Objective” means you should be able to explain the precise reason for the change. “In this sentence, the antecedent is separated from its pronoun.” “There might be too many short sentences in a row in this passage.” “The reader would be helped if the attribution were moved up in the quote.” “This paragraph isn’t in chronological order and is confusing.” “Bullet points and parallel construction could work well here.”

Any piece of writing can be changed in an almost infinite number of ways, however. Just because something can be changed, that doesn’t mean it should be changed. You are not a good editor because you can see all the possible changes. You are a good editor because you can see all the necessary changes. If the meaning is easy to understand, the writing won’t need much changing at all.

Bad editors want to change things that don’t need to be changed. They tip their hand in their explanation for their edits because they can cite no objective reason. They say something like, “I made it sound better.” “It reads smoother.” Why? “It just does.”

Usually it doesn’t sound better or read smoother — not objectively. “Sounds better” is a subjective judgement. The wannabe editors believe it sounds better because it does — to their ears. This is what these wannabe editors actually mean but don’t realize that they mean: “It sounds more like I wrote it.” Their changes sound better to their ears because we all love the sound of our own voice. My voice is uniquely beautiful to me. You have a voice, too. It’s not like mine, yet it should be respected.

When bad editors change your writing “to sound better,” they make it sound like their own voice, not like yours. In the process, they silence your voice. This may infuriate you, and it should.

You have a right to be yourself. Your writing ought to reflect your voice, and it should sound like you wrote it, not like someone else did. Good editors, if they fiddle with the voice at all, try to make the writing sound even more distinctively like the writer’s own unique, beautiful voice.

Good editors respect and celebrate the writer. They do not impose their own voice. They only change what needs to be changed. Writers love editors like that.

— Sue Burke

I’ll be at Worldcon 76, the World Science Fiction Convention, from August 16 to 20 in San Jose, California. Here’s my official schedule. I’ll also be working as staff of the Worldcon newsletter, The Tower.

I’ll be at Worldcon 76, the World Science Fiction Convention, from August 16 to 20 in San Jose, California. Here’s my official schedule. I’ll also be working as staff of the Worldcon newsletter, The Tower. HarperCollins has just published a paperback, ebook, and audiobook edition of Semiosis in

HarperCollins has just published a paperback, ebook, and audiobook edition of Semiosis in  If you weighed every living thing on Earth, what kinds of things would weigh the most?

If you weighed every living thing on Earth, what kinds of things would weigh the most?

I am a total Earthling. By that I mean I am entirely used to this planet’s environment.

I am a total Earthling. By that I mean I am entirely used to this planet’s environment.

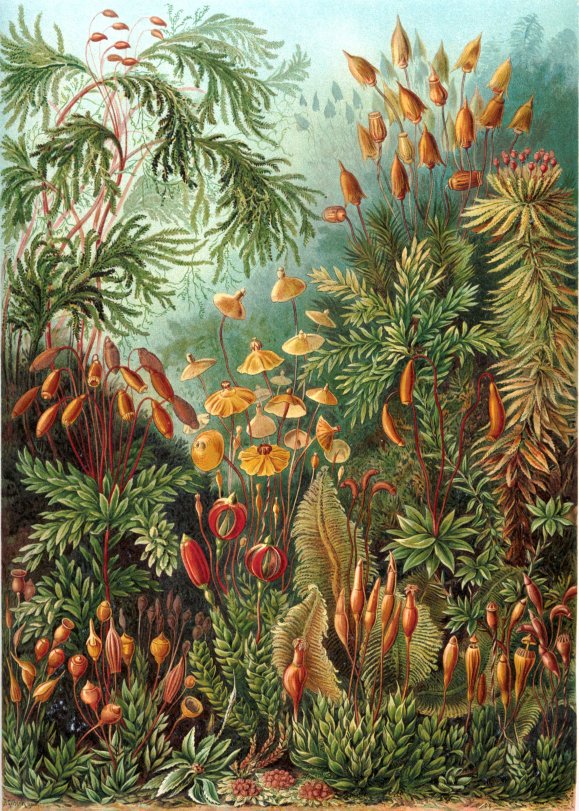

Here they are, all my houseplants, gathered for a group photo. My current apartment has few good windows, so I don’t have many plants, but they seem to be happy:

Here they are, all my houseplants, gathered for a group photo. My current apartment has few good windows, so I don’t have many plants, but they seem to be happy: The acknowledgments to Semiosis begin, “I owe thanks to

The acknowledgments to Semiosis begin, “I owe thanks to